A new JBJS study reviews costs associated with nonoperative management of osteoarthritis in the 1-year period leading up to total knee arthroplasty (TKA). JBJS Deputy Editor for Social Media Dr. Matt Schmitz offers this post on the investigation by Nin et al.

Cost containment in health care continues to be a hot topic in orthopaedic and medical research. Health utilization costs are being scrutinized across the board in the U.S. as we look to deliver high-quality care at a lower cost burden.

In the current issue of JBJS, Nin et al. present their results of an observational cohort study performed using the IBM Watson Health MarketScan databases. They reviewed 24,492 patients undergoing unilateral primary TKA for late-stage osteoarthritis over a 2-year period.

They assessed the cost of nonoperative treatments and procedures in the year leading up to TKA. These nonoperative modalities included: physical therapy, bracing, injections (either corticosteroids or hyaluronic acid along with their professional fees), medications, and knee-specific imaging.

The authors found:

- The average total cost of nonoperative procedures per patient was $1,355 ± $2,087. The total cost within this cohort: $33 million.

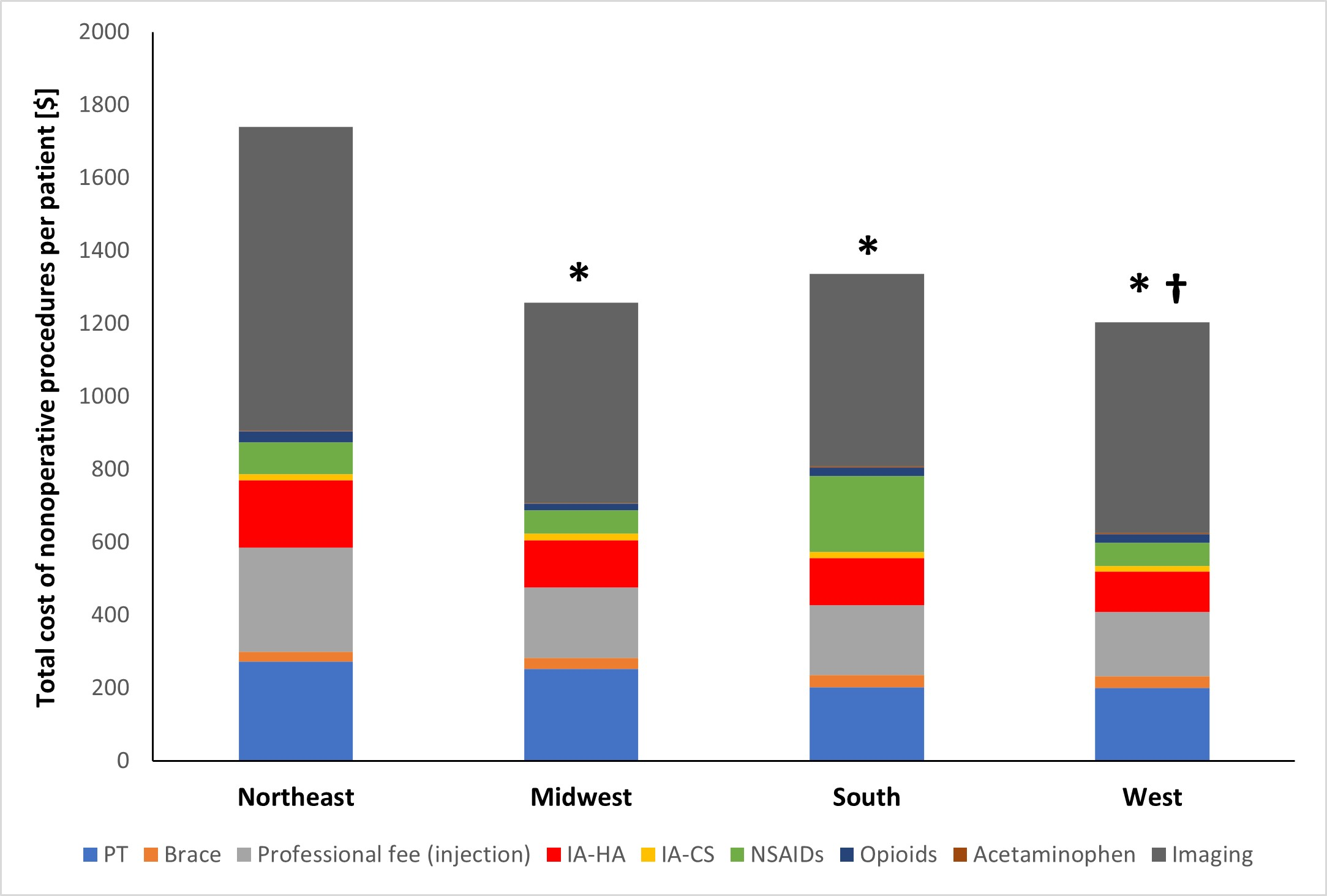

- There was substantial variation in the costs of care by region. The highest costs were found in the Northeast ($1,740 ± $2,437 per patient). Costs were lowest in the West ($1,204 ± $1,951 per patient). Costs in the Northeast were significantly higher than in the Midwest, South, and West.

- Imaging was the most common modality utilized, while the injection of hyaluronic acid was the most costly, despite not being recommended for routine use according to the most recent American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guideline (AAOS CPG).

- Opioids (despite strong recommendation against their being prescribed in the AAOS CPG) were utilized for nearly 30% of the patients.

Improving Cost-Savings

Despite the limitations of large database studies, the findings are interesting and thought-provoking. Although nonoperative modalities can absolutely be useful in patients with arthritis, one has to question the usefulness in the more immediate period preceding TKA. This could be an area to trim health-care costs.

The authors suggest that future studies should perhaps evaluate the effectiveness of nonsurgical treatments in various stages of the disease. With an estimated 600,000 TKAs performed annually in the U.S. and increasing, there is definitely potential for cost-savings in this population. Even simply following the AAOS CPG could potentially save nearly $4 million of the $33 million spent in this cohort of patients.

Access the full report at JBJS.org.

Matthew R. Schmitz, MD

JBJS Deputy Editor for Social Media

Related reading on OrthoBuzz: The Evidence Against Viscosupplementation for Symptomatic Knee Osteoarthritis; Does “Prehabilitation” Prior to TKA Help or Not?; What’s New in Adult Reconstructive Knee Surgery 2022

The fact there are regional variation in a country like the United States should not be a surprise; the states prides themselves as autonomous territories resisting federalism in many cases, despite the overwhelming patriotism to the American flag and cause.

What is a surprise is where the differences lie.

1. The use of non-operative treatments particularly hyaluronic acid injection

This study found that people from the NorthEast (NE) regions had more cost expenditures associated with non-operative measures in the 12 months prior their total knee replacements. Of interest are the costs associated with injection of hyaluronic acid (IHA) which is not recommended for routine use by the AAOS guidelines. Both the study authors and the JBJS Deputy Editor voiced concerns about this trend and speculated if more cost savings can be achieved if these variations are reduced; neither actually suggest that NE clinicians may be unnecessarily more non-operative treatments on late-stage knee osteoarthritis (OA), but the inference is there.

However we need to keep in mind that the study looked at patients who ultimately ended up with TKA, and hence by default, failed to improve substantially from these non-operative treatment, which is why they progressed to surgery. It does not consider those who had non-operative treatment for knee OA, and did not need or end up having TKA.

Hence in considering efficacy of non-operative treatment like IHA, its associated waste/cost savings, it cannot be properly assessed in absence of other more important data. For example it is also well established that there are significant variation in TKA rates across the US (1) amongst Medicare beneficiaries particularly higher in the West (W) and MidWest (MW) than the national average. One interpretation here can be physician (or patient, for that matter) “enthusiasm” for TKA as a treatment option, or lower tolerance/shorter trial of non operative management prior TKA. In this age, sex, and race/ethnicity-adjusted analysis, the regional difference is telling.

2. The use of imaging

Despite the obvious differences the study authors did not appear to define why there is a signficantly higher costs associated with imaging in the 12 months prior TKA. It may be possible that more radiographs were done during this period but it is not clear this is the case.

The question is then what other imaging modalities may be involved? MRI is a possible candidate, which raise the question for what purpose? Shouldn’t it be obvious to most clinicians that radiographs performed within 12 months of TKR for late-stage knee OA, should demonstrate advanced radiological stages of osteoarthritis?

It is possible that some patients may have radiographs with equivocal knee OA, whereas others may demonstrate rapidly progressive form of OA. However a common practice from previous generation is to ‘look’ for degenerative meniscal tear which is subsequently ‘treated’ with arthroscopic debridement. Again the study data does not allow analysis of that, and it is uncertain how many of these procedures resulted in delay of TKA as a treatment to late-stage knee OA.

In conclusion, the study offers an interesting glance to regional variation in non-operative treatment 12 months prior TKA, but it does not provide adequate information nor insight to the actual clinical practice in each region nor explain the difference they found. Granted this does not necessarily prevent any speculation or attempts at explanation, but to link this to possible costs saving certainly infers that the high-costs prior TKA can be trimmed, and indirectly singling out the NE region potentially confers certain negative innuendos, yet to be proven by the study.

I think the authors are obligated to provide more data on details on imaging, overall variable-adjusted TKA rates in each region which may vindicate some.

Reference

1. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2765054