Dr. Matt Schmitz, JBJS Senior Editor for Pediatrics and Social Media, shares this post on a new Level-I study now in JBJS.

Randomized controlled trials are hard enough to initiate and conduct in orthopaedics—having long-term outcomes from such trials is even rarer. In the current issue of The Journal, Bisson et al. report on 9-year follow-up from the Chondral Lesions And Meniscus Procedures (ChAMP) trial. In this study, conducted at The State University of New York in Buffalo, the investigators found that debridement of unstable chondral lesions during arthroscopic partial meniscectomy (APM) yields no long-term benefit over observation. Access the study and visual abstract at JBJS.org:

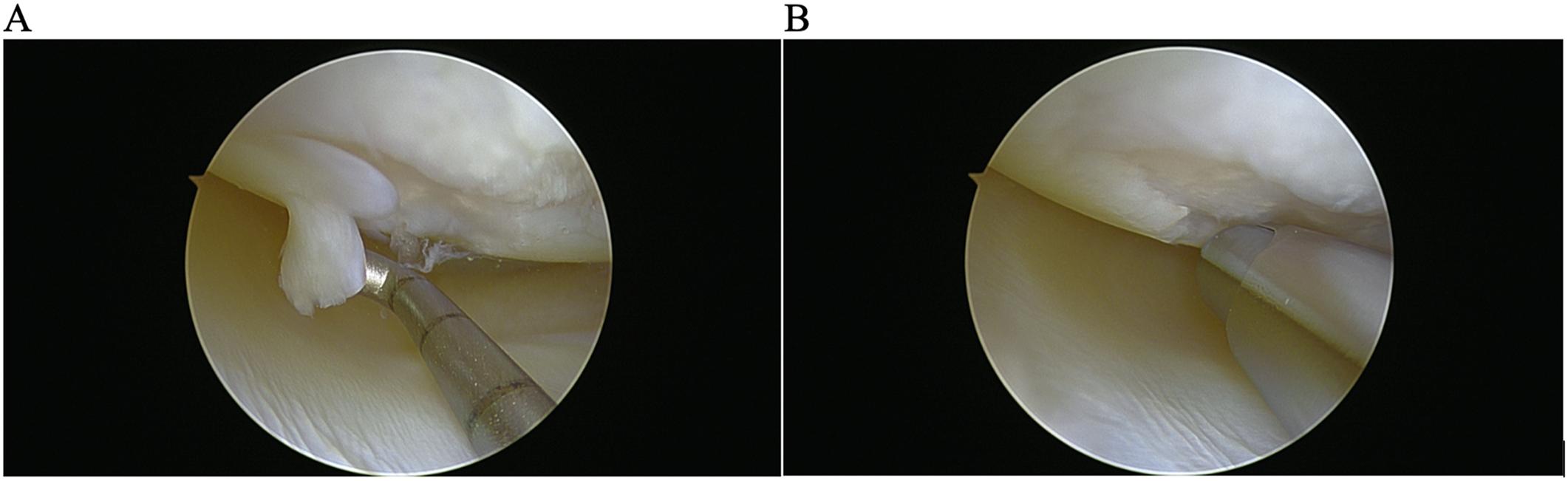

The original ChAMP trial included patients ≥30 years of age who were undergoing APM. Patients were randomized intraoperatively to debridement or observation of unstable chondral lesions (Outerbridge grade-II, III, or IV) encountered during surgery. Short- to mid-term results showed no consistent advantages of debridement beyond early differences in pain, with prior 1- and 5-year follow-ups showing no significant between-group differences in pain, other patient-reported outcomes, joint-space narrowing, or subsequent surgery.

The prospective cohort study of 9-year outcomes aimed to determine whether any long-term benefit of debridement would emerge. Methods included comprehensive patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs)—WOMAC (pain, stiffness, function), KOOS subscales (pain, other symptoms, function in sport and recreation, quality of life), VAS for pain, and the SF-36—alongside physical examination (range of motion, quadriceps circumference, effusion), and radiographic assessment of joint-space narrowing; any subsequent knee surgeries were also recorded.

Of 190 original participants, 140 were available at 9-year follow-up (64 in the observation group, 76 in the debridement group). The cohort was predominantly male (63%), with an average age of 64 years at follow-up. Twenty-five (17.9%) of the participants had had additional knee surgery on the index knee, leaving 115 for the PROMs analysis. Among those patients, 106 underwent physical examinations and 109 had radiographic data.

There were no meaningful differences between the groups with regard to demographics, with the exception of preoperative weight, which was adjusted for in analyses. No significant differences between the groups were found for PROMs (including WOMAC pain, p = 0.15), physical exam measures, radiographic joint-space narrowing, or rates of subsequent surgery.

In summary, debridement of unstable chondral lesions at the time of APM yielded no additional long-term benefit over observation as assessed at 9 years postoperatively. The findings reinforce the earlier short- and intermediate-term results, supporting a management approach of observing unstable chondral lesions rather than routine debridement during APM. Weaknesses of the study include a lack of complete follow up, but there was still nearly 75% of the original cohort evaluated at this long-term interval.

Debridement of unstable chondral lesions is common with arthroscopic meniscectomies, but the current data support the short- and mid-term results showing no benefit to debridement of the lesions. These findings from the ChAMP trial provide a scientific look at long-held beliefs in the arthroscopic management of meniscal and cartilage injuries in pre-arthritic knees. I encourage all surgeons who care for patients with these types of injuries to read the study in depth as it has the potential to change arthroscopic practice patterns.

Read the full study and access the visual abstract at JBJS.org: Debridement of Unstable Chondral Lesions During Arthroscopic Partial Meniscectomy Provides No Long-Term Benefit. Patient Outcomes 9 Years After the Original ChAMP Trial

Additional perspective is offered by Hauer and Mauro in a related commentary article: To Debride or Not to Debride–That Was the Question

JBJS Senior Editor for Pediatrics and Social Media