There is a long-standing crisis in the field of orthopaedics with respect to diversity, equality, and inclusion. It rightly has garnered press, including research articles and editorials, is the focus of discussion at meeting symposia, and is generating conversation across social media. Yet, while some initiatives have made incremental improvements in diversity with regard to gender, more work remains. And our field remains woefully behind other medical specialties in expanding our ranks of colleagues to include underrepresented minority (URM) surgeons and clinicians.

In a two-part investigative report for STAT, journalist Usha Lee McFarling provides an in depth look at the lack of racial and ethnic diversity in orthopaedics, including interviews with several orthopaedic surgeons who share their first-hand experiences of obstacles encountered when joining the field (part I: “The Whitest Specialty: As Medicine Strives to Close Its Diversity Gaps, One Field Remains a Stubborn Outlier” and part II: “Orthopedic Surgeons Pride Themselves on Fixing Things. Can They Fix Their Own Field’s Lack of Diversity?”)

As noted in the report, fewer than 2% of those practicing in orthopaedics are Black, 2.2% are Hispanic, and 0.4% are Native American.

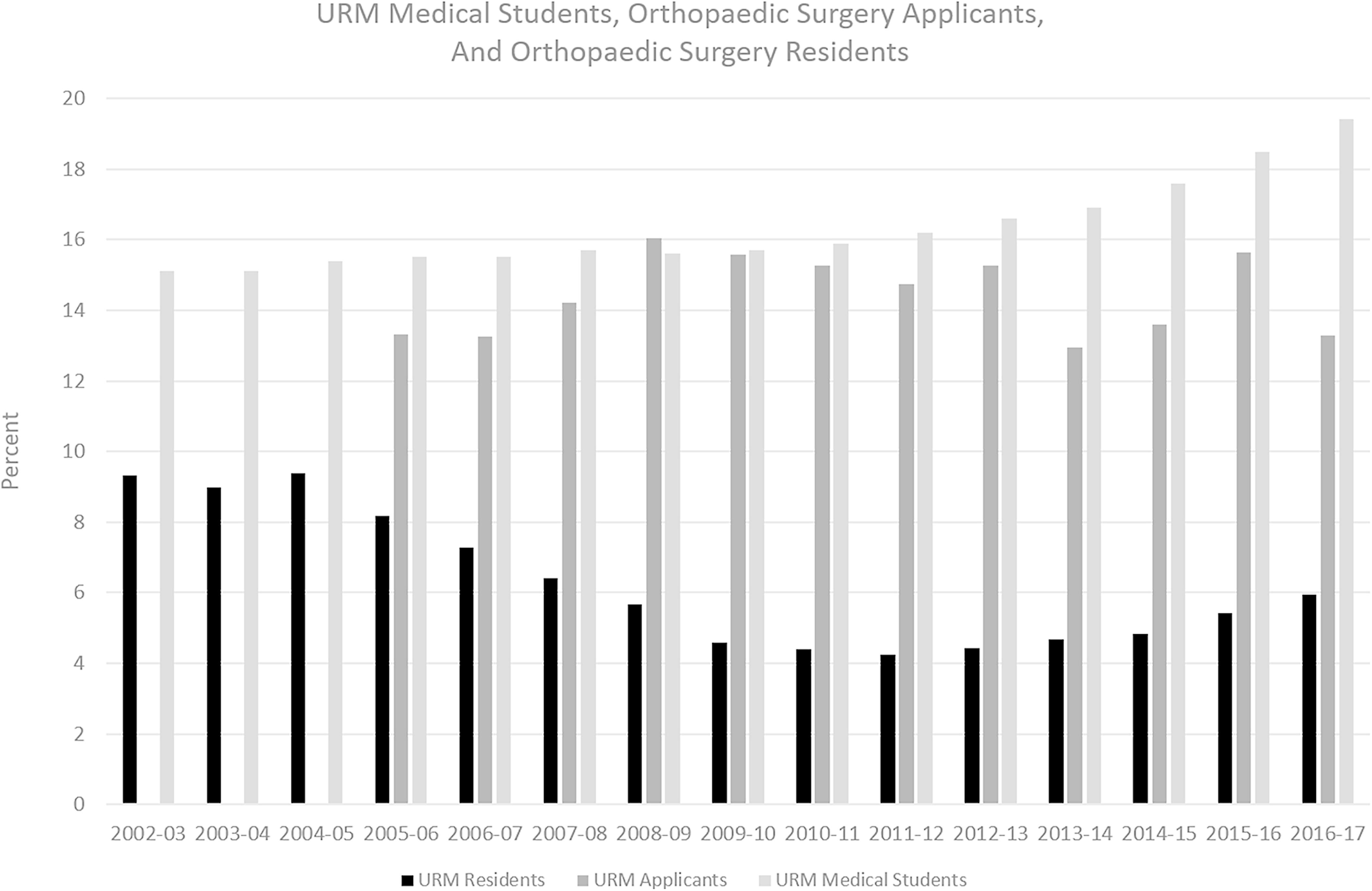

The report highlights that the problem is clearly multifactorial. Despite initiatives and efforts to improve diversity, there was a decrease in the number of URM residents in orthopaedics from 2002 to 2016, with an increase in number of programs without a single URM resident during the same period.

Not only does the pipeline into orthopaedics have barriers that Black, Hispanic, and Native American candidates must overcome, the pipeline also has leaks in the journey toward becoming an orthopaedic surgeon. A 2011 study found that, in orthopaedics, there were 13.5 White applicants for each Black applicant and 14 White applicants for every Hispanic applicant, disparities much higher than found in general surgery. And despite representing only 5% of current residents, Black residents accounted for 43% of those who were fired or dismissed in 2015, clearly showing that inequities are not in the admission process alone. The report notes that many White candidates wash out as well but that statistics show that “at every level,” the road is more difficult for underrepresented candidates.

The profound lack of representation contributes to a lack of mentorship for potential orthopaedic candidates of color. The lack of mentorship also likely factors into a lower rate of matching into orthopaedics, as some candidates are excluded from learning the ways “to play the game” in earning a residency slot. Between 2005 and 2014, 73% of White applicants matched into orthopaedic residencies compared with 46% of Black applicants.

There are no easy answers to this problem. But the unflinching reporting in these articles shows that there are some hard truths that we as a community need to acknowledge and must find ways to overcome. Notes the reporter, “With the numbers currently so small, people interviewed for this series say these racial demographics will be nearly impossible to change without focused, intentional, and consistent effort across the field, from medical schools and hospitals to residency training programs — and it will require buy-in and hard work from the field’s white majority, who hold the power and almost all the leadership positions.”

I implore all orthopaedic surgeons to read this two-part report as a first step in acknowledging the problem and working toward solution. As aptly stated at the close of the report by Dr. Augustus White III, a barrier-breaking physician who was Stanford’s first Black medical student, Yale’s first Black orthopaedic resident and professor of medicine, and Harvard’s first Black teaching hospital department chief, “Orthopedics has to do better.”

Matthew R. Schmitz, MD

JBJS Deputy Editor for Social Media

Figure reproduced from: Adelani MA, Harrington MA, Montgomery CO. The Distribution of Underrepresented Minorities in U.S. Orthopaedic Surgery Residency Programs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019 Sep 18;101(18):e96