When patients present with identified bone metastases, a known primary diagnosis, and pain, the orthopaedic surgeon is nearly always contacted. The treatment plan is guided by a shared decision-making process involving the patient, surgeon, oncologist, and other clinicians. When a lesion is associated with a complete bone fracture, intramedullary fixation spanning the bone is often the next step, unless the diagnosis is extremely dire and the patient has opted for palliative care only. However, when a lesion is identified on imaging and the bone is structurally intact, the decision gets more complicated. Will pain from surgical fixation exceed that caused by the lesion? Should we use radiation therapy or chemotherapy first and wait and see if the lesion produces a complete fracture?

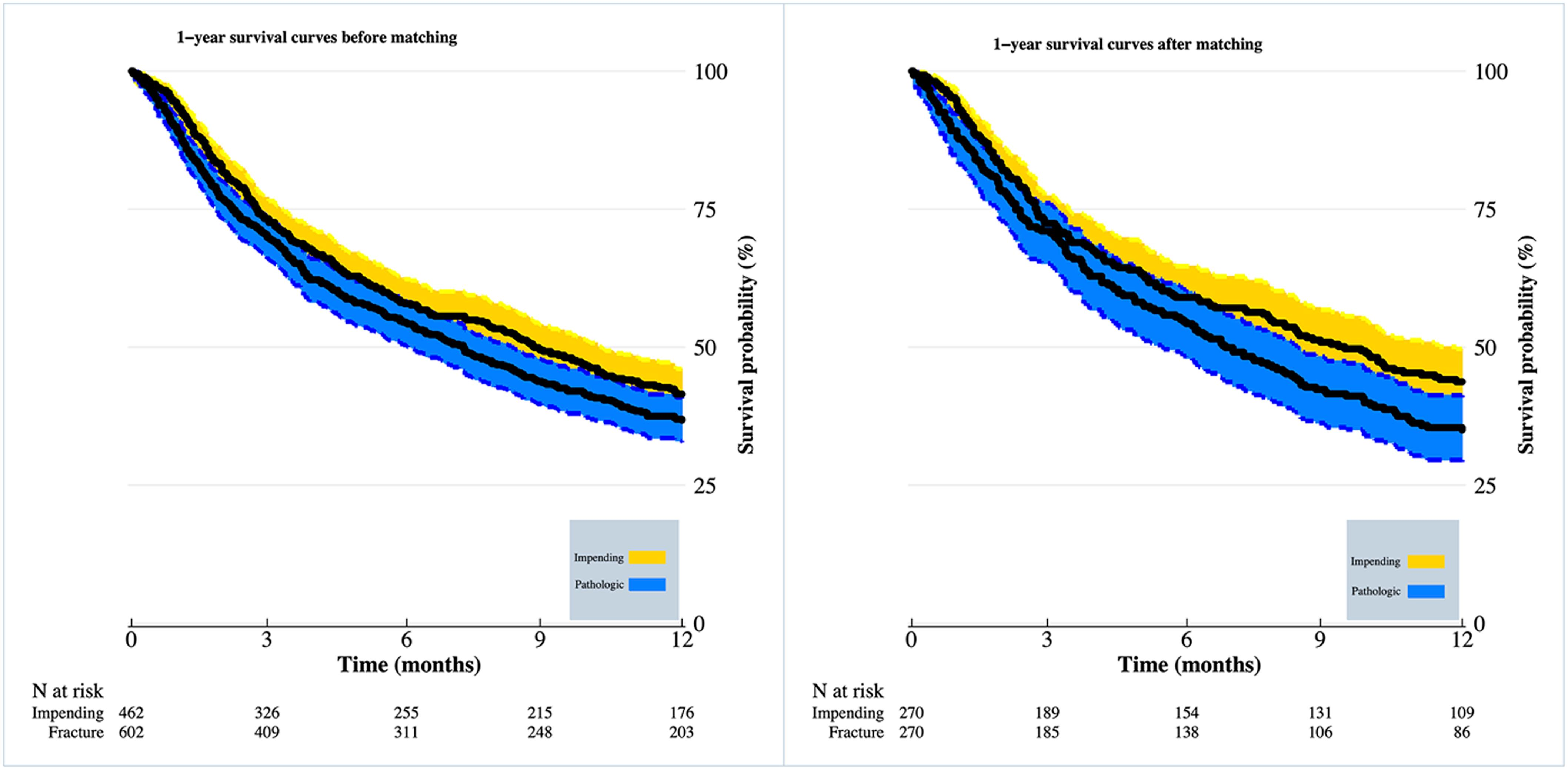

In a recent JBJS study, Groot et al. examine differences in clinical outcomes of patients with metastatic disease treated operatively for impending vs. completed long-bone fractures. Using a database of >1,000 surgical patients, the investigators matched patients on the basis of numerous key characteristics, including primary tumor growth type, tumor location, and other metastases, ultimately including 270 impending and 270 completed pathological fractures in their analyses.

Although the authors identified no significant difference in the 90-day survival rate (71% for the completed fracture cohort vs. 73% for the impending fracture cohort), they found a meaningful difference in the 1-year survival rate, which was worse for the completed fracture group (38% vs. 46%). In addition, better secondary outcomes were seen for patients treated for impending fractures, including less intraoperative blood loss, fewer perioperative blood transfusions, shorter anesthesia time, and fewer reoperations.

Information in this study could be helpful in counseling patients with metastatic disease regarding the option of prophylactic surgical stabilization. It does not, however, address the question of whether a patient might do as well without surgery. As the authors point out, it is imperative to properly identify which lesions are at risk for fracture in order to prevent unnecessary surgical intervention, with practical and more accurate prediction tools needed. One must also consider that the patients who presented with fracture may have had more advanced or more aggressive disease leading to the 1-year mortality difference.

Nevertheless, this study advances our knowledge in the area of long-bone metastatic disease for the benefit of patients and their families when making important care decisions.

Click here to access a downloadable Infographic summarizing this study.

Marc Swiontkowski, MD

JBJS Editor-in-Chief