A new study in JBJS examines noise levels during cast removal. In this post, JBJS Editor-in-Chief Dr. Marc Swiontkowski reflects on the importance of research that explores workplace safety and occupational risks to orthopaedic personnel.

Occupational medicine as a field of expertise provides great value for patients and their employers alike. The body of scientific literature supporting this area of medicine in the orthopaedic space tends to be focused on spine injuries and upper-extremity repetitive injuries, often in the realms of manufacturing and desk work.

There has been painfully (apologies for the use of that word) not enough work conducted in the area of risk to medical personnel. We have begun to learn more about stress and burnout, in part fueled by the stresses of the COVID 19 pandemic. We also have some data on occupational injury involved with lifting and transporting patients as well as on the risk of needle sticks. And there is robust literature on the risks of radiation exposure with the use of fluoroscopy in our field of orthopaedic surgery. But there is room for further investigation into other aspects of orthopaedic care.

Adding to the literature is a new JBJS study by Shaw et al. on noise exposure during cast removal. Cast removal is a fundamental task in fracture treatment. As the authors note, the noise generated by cast saws is considered safe according to the standards of the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. However, they point out that the limits of safe noise exposure are not universally agreed upon. Potential noise-induced hearing loss from long-term or repeated exposure (to cast saws or surgical power tools) is an issue worthy of our understanding.

Study Details and Findings

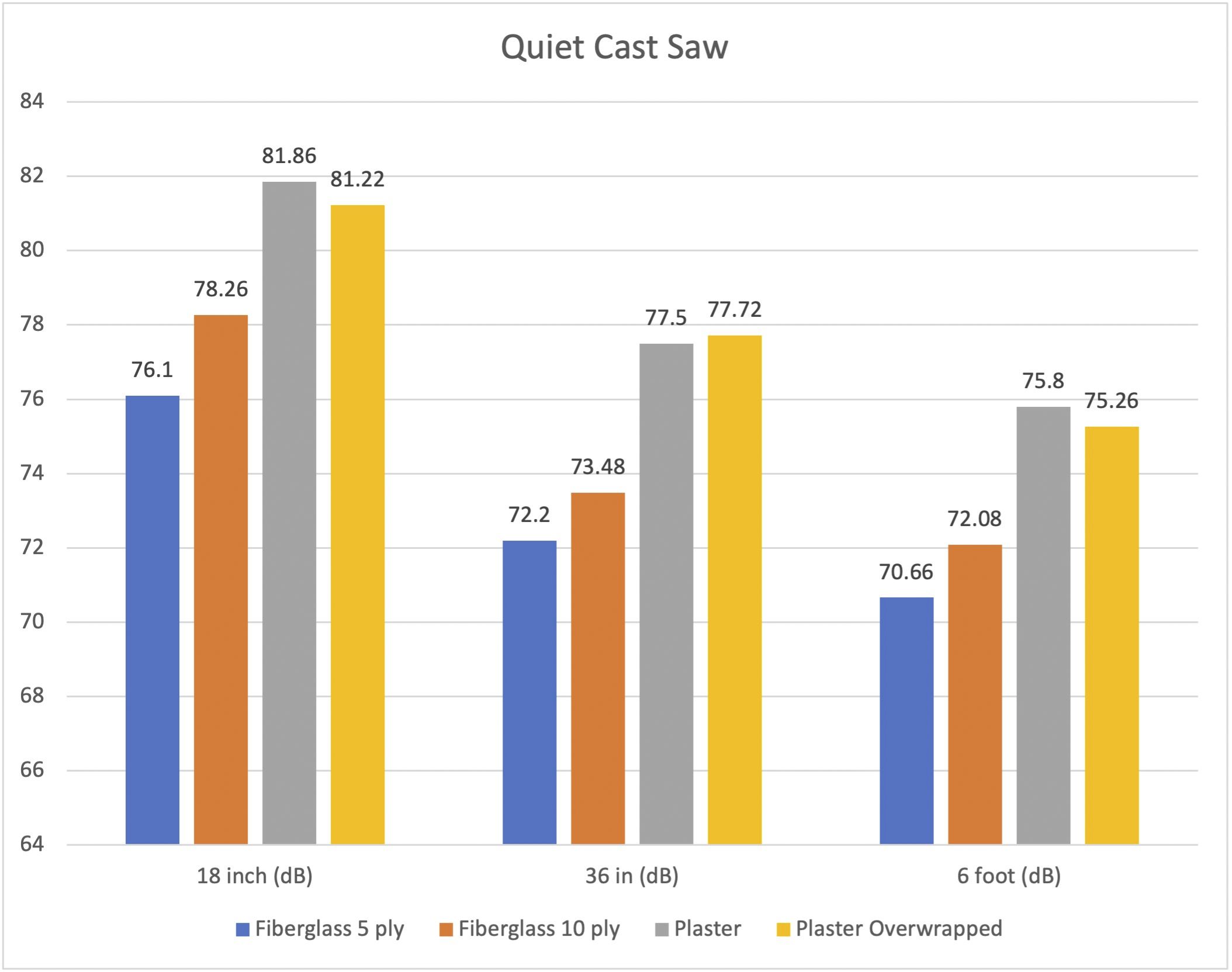

A simulated arm model was used. Samples were tested using a standard cast saw and a quiet saw. Noise levels were measured at 18, 36, and 72 inches (20, 91, and 183 cm) from the saw.

The researchers tested 4 different conditions:

(1) Fiberglass casting material with 5-ply thickness;

(2) Fiberglass casting material with 10-ply thickness;

(3) A plaster splint with 10-ply thickness;

(4) A plaster splint with 10-ply thickness and fiberglass overwrapping.

They found that plaster material demonstrated significantly greater noise levels than fiberglass at all distances for each type of saw. Increasing fiberglass thickness significantly increased noise levels. The use of a quiet saw vs. standard saw significantly decreased noise generation.

As concluded by the authors, “Occupational noise exposure can be mitigated with the use of fiberglass casting material that is not >5 ply in thickness, with a quiet cast saw for removal. The use of a quiet cast saw substantially decreased noise exposure to patients and staff members over standard orthopaedic cast saws.”

In general, most orthopaedic surgeons are not directly involved with cast removal on a frequent basis, but our colleagues working with us in the outpatient setting definitely are. We should encourage the use of ear-protection gear for our staff as well as for patients.

It is my hope that manuscripts like this will prompt investigations into other areas of occupational risk for those of us caring for patients with musculoskeletal injury or disease.

Access the report by Shaw et al. on JBJS.org.

Marc Swiontkowski, MD

JBJS Editor-in-Chief

Related reading on OrthoBuzz: Reducing Intraoperative Breast Radiation Exposure of Orthopaedic Surgeons; How Much Radiation Does a Surgeon’s Brain Receive during Femoral Nailing?