In this post, JBJS Deputy Editor for Social Media Dr. Matt Schmitz reflects on technology-assisted surgery and skills acquisition in orthopaedics.

One of the key foundations of academic orthopaedics is teaching the next generation how to become competent and independent surgeons. This involves imparting surgical knowledge as well as guiding residents and junior surgeons on the use of tools that may improve their surgical outcomes.

In the 1980s, researchers Stuart and Hubert Dreyfus described a pathway of skills acquisition by which a learner progresses through stages, from novice to advanced beginner, then to competent, proficient, and finally, expert1,2. With the expansion of technology use in orthopaedics, it’s logical to ponder how those tools may assist with skills acquisition among junior surgeons and thus theoretically improve their surgical consistency and outcomes. Advocates of computer navigation for joint arthroplasty, for example, tout more reliable implant placement. Advances in technology in surgery could theoretically help novice and advanced-beginner surgeons progress to competent.

Looking further at the topic, what about the value of technology use (computer navigation and robotics) among lower- versus higher-volume surgeons? As McAuliffe et al. point out in a new study, prior research regarding the use of technology in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) primarily has focused on high-volume settings, leaving uncertainty about the benefits of technology-assisted TKA for those who perform fewer procedures. Their study is in the November 20, 2024 issue of JBJS:

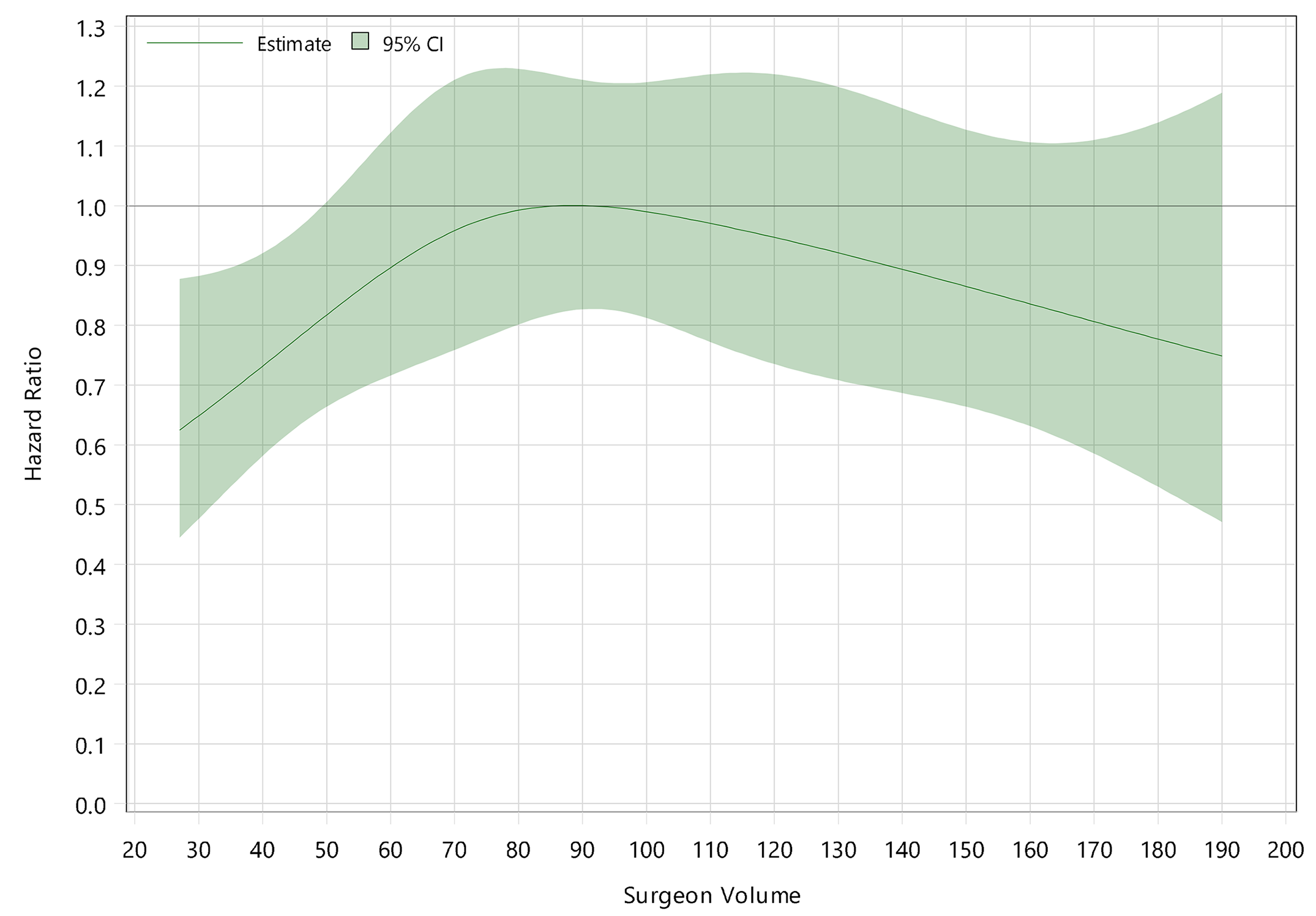

The researchers investigated the association of technology usage and surgeon volume on revision rate in TKA. Using data from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR), they included 53,264 primary TKAs performed from 2008 through 2022, by surgeons 5 or more years after their first recorded procedure. The analysis assessed the relationship between surgeon volume, the type of instrumentation used (technology-assisted or conventional instrumentation), and revision rates. Kaplan-Meier estimates and Cox proportional-hazards methods were applied to evaluate outcomes.

The researchers found that:

- Among the analyzed TKA procedures, 31,536 were technology-assisted and 21,728 involved conventional instrumentation.

- The use of technology lowered the all-cause revision rate for surgeons performing fewer than 50 TKAs annually and reduced the minor revision rate for those with fewer than 40 TKAs per year.

- No interaction was found between surgeon volume and major revision rate.

- When using 100 TKAs/year as a benchmark, lower-volume surgeons had higher rates of all-cause and major revision with conventional-instrumentation TKA but rates comparable to those of surgeons performing 100 TKAs/year with technology-assisted TKA.

The main take-away, say the authors, is that technology-assisted TKA was associated with a lower revision rate than TKA with conventional instrumentation for lower-volume surgeons, suggesting that its preferential use may enhance surgical outcomes for this group. In contrast, no significant difference in revision rate between TKA with technology assistance versus conventional instrumentation was found for higher-volume surgeons. The findings indicate a potential strategy for improving outcomes in low-volume settings through technology utilization, with further studies warranted.

This research underscores the importance of tailoring surgical technology applications to surgeon experience levels, particularly in improving patient outcomes for lower-volume TKA surgeons. In certain practice scenarios in which surgeons simply can’t obtain the volume to become proficient (novices or advanced beginners), it seems as though technology could be helpful to surgeons in advancing to the competent level. At the same time, however, overreliance on technology could take away from “learning” the basics of surgical procedures, which involves repetition. Would overreliance prevent a surgeon from becoming proficient or expert? While future studies will help shed further light on technology use, for now, we see from the study by McAuliffe et al. that technology-assisted TKA has the potential to improve outcomes for lower-volume surgeons.

Read the study at JBJS.org: Association of Technology Usage and Decreased Revision TKA Rates for Low-Volume Surgeons Using an Optimal Prosthesis Combination. An Analysis of 53,264 Primary TKAs

JBJS Deputy Editor for Social Media

References:

- Dreyfus SE., Dreyfus HL. A Five-Stage Model of the Mental Activities Involved in Directed Skill Acquisition. Washington, DC: Storming Media; Dec 1980. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA084551.pdf. Archived from the original on May 16, 2010: https://web.archive.org/web/20100516071752/http:/www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA084551&Location=U2&doc=GetTRDoc.pdf

- Dreyfus S, Dreyfus HL. Mind over Machine. Free Press, New York (1998).

It is important to differentiate the idea of low-volume, lower-volume and higher* volume surgeons for a particular operation, in this case, total knee arthroplasty. (*as opposed to “high-volume”)

Historically in most US literature, low-volume surgeons are labelled for those who do less than 20 operation of a specified type in a year, and this threshold is often used in non-orthopaedic surgical specialties. However there is a wide range of what is considered low volume for surgeons performing TKA, although there is some consensus that this may involve 50, 70 or 100 TKA annually depending on contemporary literature, many published in the last 5 years.

I think the focus should be what high- (or higher-) volume practice should be, as threshold of 50, 70 or 100 TKA per year should be defining rather than labelling those who does not reach these as low- or lower-volume surgeons. What is definitely established here in this study is that high volume surgeons does not appear to benefit from technology when using revision as a benchmark, and that technology appears to improve the revision rate of TKR performed by lower-volume surgeons to be similar to high volume surgeons. The issue is then where the reduction in revision is happening – by indication for revision.

It is important not to “shame” those who are not “high volume” surgeons by annual case, simply by the application of “low-volume” (as the title of the orthobuzz post) or “lower-volume” label, as the AONJRR used as deliberate efforts to avoid overt negative connotation.

Afterall the reason for higher revision rate for “low volume” surgeons may not be straight forward, it may have more to do with institutional services and set up rather than the surgeons themselves. In a study by Jay R Lieberman’s group published in 2024 (DOI: 10.1016/j.arth.2024.10.136) they have found “after taking confounding variables into account, low-volume surgeons at high-volume hospitals had lower rates of PJI relative to their counterparts at low-volume hospitals (THA 0.67 versus 0.80%, adjusted odds ratio = 0.69 [95% confidence interval = 0.54 to 0.88], P = 0.002; TKA 0.51 versus 0.69%, adjusted odds ratio = 0.73, [95% confidence interval = 0.61 to 0.87], P = 0.007)”, thus concluding “increasing institutional case volume may mitigate the increased risk of PJI associated with low annual surgeon case volume.”.

Which is why I suggested the reason for revision in lower-volume vs higher-volume surgeon matters a lot in formulating conclusions based on volume and technology and their interaction with confounders.

Dr Shyan Goh

MBBS, FRACS

Sydney Australia